Are you Saving Enough?

The core reason the financial services industry exists is to help people determine if they’ll have the money to meet their goals. Raise your hand if you identify with any of these statements:

“I can’t wait to get back to eating Ramen after my bus ride back from the doctors office.”

“I never thought there were so many ways to prepare cat food for human consumption.”

“My kids can’t wait for me to move in with them.”

“You can’t outlive your money if you never had any to start with.”

Of course not. You’re reading a personal finance article because you want to make sure you achieve your goals, reduce/eliminate money worries, and avoid becoming a burden to others because you didn’t adequately save for your retirement years.

But how do you know if you’re saving enough? Are you on track? Which of the financial pornographers on cable TV should you pay attention to?

The reality is that no single metric is going to work for everyone. Oh, and all planning is for an unknown and constantly changing future such that perfect planning today can still go to pot tomorrow. Yet, if we aim at nothing, we’ll hit it every time. So, let’s try to pick this problem apart a bit.

Assumptions

When my first girlfriend was debriefing me on why I was getting disenrolled from the program with her, she pointed out, “When you assume, you make an ass out of ‘u’ and ‘me’.” I thought about debating her on the grammatical correctness of her point, but you can imagine there were other issues at hand. She did make the point that assumptions are fraught.

In military planning schools we learn that we should only make assumptions if there’s no way to source truth data or force an outcome and, the assumption is vital for planning to continue. We assume the tanker will be in the track. If it’s not, we can’t get to the target with enough gas to get home and such…

Assumptions are crucial in retirement savings planning. We must make them, and they weigh heavily on how much we should save. Assumptions we must make include:

- Pension – Will it pay as planned or shrink due to an employer’s poor planning?

- Social Security—There’s a whole list here…

- Will it pay as projected or shrink?

- Will more of it be taxed? At different/higher rates than other income?

- Could it be means-tested?

- How long will we work and at what income level prior to claiming it?

- What age(s) will we claim it?

- How long do we expect to live?

- Health Care Costs—What’s reasonable? Could they increase?

- Long-Term Care—Will we need to self-fund it? For how long? How much per year?

- Inflation—What rates of inflation do we expect for general expenses? Health care? Taxes?

- COLAs—What sources of income (e.g., pension, Social Security, VA Disability) will get regular cost of living adjustments? Which sources won’t?

- Savings rate until retirement—How much could we possibly save and still have an acceptable standard of living?

- Investment returns—What asset classes will have what returns?

- Taxes—What will rates do? What state will I live in?

This list could probably keep going, but there’s an article to write, so let’s get on with it. Your assumptions can change of course, but you will need to make them. If you skew worst case with all your assumptions, you’ll probably die with a big pile of dollars and a small pile of memories. If you go crazy with the rose-colored glasses, your future could be a couch in your kids’ basement with the occasional splurge for Alpo. The assumptions matter. A lot.

Tools of the Trade

The absolute best tool to use for determining the right amount to save for retirement is a functioning crystal ball. If yours works, please give me a shout. After ruling out supernatural foresight, the hierarchy of tools for retirement projections looks like:

Simple online savings calculators. Tools like this can determine what your savings will grow to with a specific starting amount, periodic contributions, an expected rate of return, and a retirement date. They’re good for estimating account balances but they don’t incorporate many variables or assumptions.

Simple homemade spreadsheets. Depending on your skill with a spreadsheet, you might be able to include more variables in a spreadsheet. You can change variables to account for things like raises or getting kids off your payroll. Like all such tools, they’re GIGO—garbage in, garbage out. You have to avoid both bad assumptions data and bad calculations.

Advanced online retirement calculators. Increasingly, tools are appearing that can incorporate more complex variables such as tax rates, Medicare, and Social Security claiming, etc. These tools are seductive to DIYer’s because they suggest that you can get professional-level analysis and output without paying the going rate for a financial planner.

Advanced homemade spreadsheets. If you’ve earned your advanced spreadsheet blackbelt, you might be able to design a professional-level tool to rival what advisors have access to. Good on you! It may still be worth a second opinion, but if you can code in Microsoft Excel with one hand tied behind your back, chance are you’re on a good path.

Financial Advisor tools. To the chagrin of many advanced DIY retirement planners, tools like E-Money, Money Guide Pro, and Right Capital are only available to financial professionals. These tools excel at integrating all aspects of retirement planning because they not only include up-to-date tax and other law-related planning factors, they also natively show how one or more changes to a projection ripple across your financial future.

For example, if you buy an RV at age 55 with funds from your taxable account or Traditional IRA, will it increase your lifetime tax burden in the way that you sell assets to fund it? And how does this change how much you’ll be able to leave for your kids or have for long-term care funding? What happens if one spouse passes away early? Does the plan perform better because there’s less consumption and an infusion of life insurance or does the loss of retirement savings horsepower increase the probability of outliving your wealth?

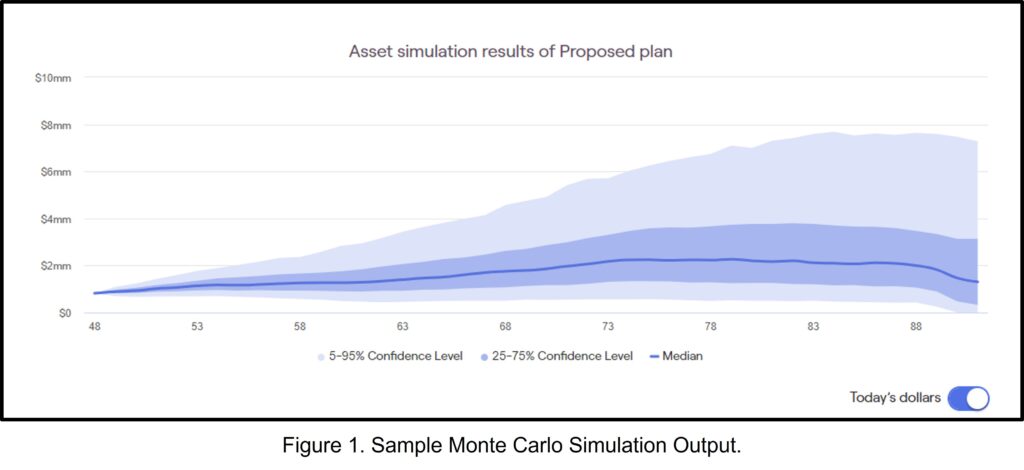

Finally, advisor tools incorporate Monte Carlo simulations. These probability simulations typically consist of 1,000 or more randomized sequences of market return to help you understand when and how your probability of funding your retirement might change or become problematic.

While still lacking in crystal ball functionality, advisor tools can give you the sense that you at least tried to consider all relevant variables in your planning. Ideally, use of an advisor tool came with a great advisor that helped you through a thorough planning process.

Savings Targets

Regardless of the tool(s) you use, you may want to start with an understanding of various methods for developing a savings rate. None of the following methods are rules of physics, but each can be useful. Ultimately, the method that resonates with you might be the best one—at least to start with.

10% to 20% Saving a percentage is a great place to start. When it comes to employer plans like TSP/401(k)/403(b), they’ll insist you defer a percentage of your pay rather than a dollar amount.

Humans usually feel dollars, but we can think percentages. If we spend $100 on a meal, we compare that to what other meals cost and we feel the bargain or lack thereof. If we spend .0058% of our monthly income on a meal out, what does that really mean? Did we get value? Is that what we usually spend? There are times when dollar amounts are useful to think in, other times we ought to think in percentages.

A percentage savings target also grows with raises and inflation. If you save $6,000 per year instead of 6%, you might be more inclined to skip the increases in savings that your future self would certainly appreciate.

Picking the right percentage is the $64K question and it requires tools and assumptions as discussed above. That said, you’ll rarely hear an expert who works with savers day-in, day-out suggest anything less than 10%.

But wait—is that 10% of gross income or take-home pay? It does matter, but if you’re not anywhere close to 10% just get to one of them at max forward velocity, then go back and refine your analysis of gross versus net.

The higher your saving percentage, the sooner you get to retire, and/or the better funded your retirement will be. Ten percent is a good starting argument, but you’ll need to modify for factors like:

- Started later than late 20’s: Save more.

- Want to retire before mid-60’s: Save more.

- Want to retire before 50’s: Save a lot more.

- Live frugally and have two military pensions: Maybe save less.

- Etc.

If you don’t have time to engage in 6-DOF models of retirement savings and just want to pick a number, perhaps start with 10% and increase 1% yearly until you have time conduct more thorough analysis?

Enough to get the employer match. If your employer matches your TSP/401(k)/403(b) contributions, failure to contribute up to the match (e.g., 3%, 5%, or 6%) is asking for a pay cut. You are voluntarily reducing your compensation. While it’s a rare family that will have enough nest egg from just saving at the employer match rate, the employer’s match creates a great floor.

Brand new workers with student debt might be eating Ramen just to save the match. This is the reality of our system where most employees are required to fully fund their own retirement (e.g., no employer pension and a gold watch). If you can only do the employer match level, prioritize increasing by a percentage or more each year as income grows and debt shrinks (you’ll want your debt to shrink…).

Enough to get to 4% “safe withdrawal rate” by a given age. If you’ve sniffed down the rabbit hole of “How much is enough?,” you’ve probably come across the terms safe withdrawal rate or 4% rule. While the words safe and rule need to be read as “reasonable starting point for analysis, not specifically safe” and “guideline, not rule,” these terms describe the idea that a great body of evidence and analysis suggest that one can start a 30-year retirement by consuming 4% of a nest egg that’s invested in 50% stocks, 50% bonds. Each year, you can increase the prior year’s amount by inflation. Approximately 95% of scenarios would not have you outlive your money.

When you’re in your accumulation years, this is a great target to aim at. As soon as you start to really flesh out goals and understand your retirement income needs, this method is probably too squishy to rely upon. But when you’re in your 30’s and 40’s and just want to have ballpark figure, it’s nice to say, “I’ll need $1M for every $40K of inflation-adjusted income I want each year.”

If your military pension and VA disability will account for say, $80K, and you expect a total of $40K for you and your spouse, and you’d like to spend a total of $200K per year, then you’d need a ballpark nest egg of $2M. Again… this should be considered bar napkin math, not the analysis you want to pour into “Will I have to eat cat food?”.

Enough to get to 25x spending. If you’re a F.I.R.E. (Financial Independence, Retire Early) aficionado, then you’re likely familiar with the target number of 25 times spending as its part of the core dogma. Good news—if you read the last paragraph, you’re in the same place… sort of.

If annual spending is $40K, then 25x is $1M. The 25x rule is just the 4% rule with some nifty sorcery called “algebra” thrown in.

!!!WARNING!!!

In addition to the potential downsides of not having professional purpose for four to five decades, you should be aware that the Trinity Study analysis that contributed to the 4% guideline was for a 30-year retirement. This Vanguard study takes a look at a F.I.R.E. retirement using 4% to suggest that F.I.R.E. types can’t use a traditional 4% with a form-fit replacement or fire-and-forget mindset. If you’re thinking about going en fuego, dive really deep on your assumptions…

Enough to be an AAW or PAW. In the 1996 book The Millionaire Next Door, authors Stanley and Danko coined the terms Average and Prodigious Accumulators of Wealth or AAW and PAW.

An AAW has a net worth of:

Age times Pre-tax Income divided by 10.

For example, a 40 year-old with pre-tax income of $150K should have a net worth (own minus owe) of $600K.

A PAW, a super saver of sorts, would have twice what an average accumulator would have.

Brian Preston of the Money Guy podcast suggests that for younger savers, the AAW and PAW formulas are dishearteningly unachievable for most. He offers a good modification for those under age 40 that haven’t had a lot of years for compounding to take effect yet:

Age times Income divided by (number of years until age 40, plus 10).

For example, a 25-year-old making $80K should have a net worth of about $80K. Formulas like these can be nice “vector checks” to see how we’re doing, but they can be arbitrary and devoid of context. If you’re aiming to Die with Zero, just stacking Benjamins to match a number can put you in the grave with a big pile of dollars and a small pile of memories and fulfilling experiences.

Perhaps consider the AAW and PAW numbers as context, but not the whole story.

Enough to say yes to the truly important things. If you count yourself more in the “experiences” than “stuff” camp, then saving enough to be able to afford what really counts, e.g., taking the grandkids to Disney or a Broadway show, may be more important than remodeling the kitchen. If you’re already frugal, perhaps designing your savings goals around what will make an awesome pile of memories is the way to build your savings targets. You may have a hard time spending past your frugality, but at least you can build a plan centered on spending where it counts first.

Enough to cross money off the worry list. If you or your spouse can’t not worry about having enough money, consider focusing your savings target on producing enough secure income such that your “minimum dignity floor” could be covered. This might look like stacking military pension + VA disability + Social Security + Annuities/Bond or CD Ladders. Sometimes called a “safety first” plan, this method assumes you’re okay not running up the scoreboard on your retirement nest egg, you just want to make sure your true needs will always be covered.

Enough to replace XX percent of your pre-retirement spending. A common platitude has been that you’ll want to spend between 80%-100% of your pre-retirement spending during retirement. This is probably true during the early “go-go” years of retirement when our bodies and energy afford us the health to travel and stay active. However, 80%-100% is a wide range and it could still be wrong. You might want to spend 120% for the first five years on some great travel, but 70% for the following 5 years as you help take care of grandkids part of the year. A percentage target leaves a lot of homework incomplete and could leave you well over- or under-funded.

Cleared to Rejoin

You read personal finance articles to max-perform your dollars. Saving isn’t as fun as spending for most of us, but we need to do both. You probably put some level of calculation into your spending choices, but you’ll need to put a lot more into your saving choices. None of us wants to outlive our money or be a burden to others, so getting clear-eyed about your saving should be high on your targeting list today!

Fight’s On!

Winged Wealth Management and Financial Planning LLC (WWMFP) is a registered investment advisor offering advisory services in the State of Florida and in other jurisdictions where exempted. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training.

This communication is for informational purposes only and is not intended as tax, accounting or legal advice, as an offer or solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, or as an endorsement of any company, security, fund, or other securities or non-securities offering. This communication should not be relied upon as the sole factor in an investment making decision.

Past performance is no indication of future results. Investment in securities involves significant risk and has the potential for partial or complete loss of funds invested. It should not be assumed that any recommendations made will be profitable or equal the performance noted in this publication.

The information herein is provided “AS IS” and without warranties of any kind either express or implied. To the fullest extent permissible pursuant to applicable laws, Winged Wealth Management and Financial Planning (referred to as “WWMFP”) disclaims all warranties, express or implied, including, but not limited to, implied warranties of merchantability, non-infringement, and suitability for a particular purpose.

All opinions and estimates constitute WWMFP’s judgement as of the date of this communication and are subject to change without notice. WWMFP does not warrant that the information will be free from error. The information should not be relied upon for purposes of transacting securities or other investments. Your use of the information is at your sole risk. Under no circumstances shall WWMFP be liable for any direct, indirect, special or consequential damages that result from the use of, or the inability to use, the information provided herein, even if WWMFP or a WWMFP authorized representative has been advised of the possibility of such damages. Information contained herein should not be considered a solicitation to buy, an offer to sell, or a recommendation of any security in any jurisdiction where such offer, solicitation, or recommendation would be unlawful or unauthorized.